By Adam MacKinnon, Former Editor of Summerfield Messenger

As a Waldorf parent, I’ve long been fascinated by chalkboard drawings, curious to understand why they’re such a feature of the grades classroom. And I’ve seen the devotion and hours spent trying to get a picture just right in the hectic time before a new block, and wondered why teachers put themselves through all that angst!

To learn more, I spoke with three experienced local teachers, all of whom have not only taken classes through grades 1-8 (teacher looping), but they also taught chalkboard drawing in Waldorf teacher-training.

Many thanks to Laurie Tuchel (Credo High School), Jamie Lloyd (Woodland Start Charter School), and Saskia Pothof (Summerfield Waldorf School & Farm) for allowing me to interview them for this article.

Why have Chalkboard Drawings evolved into such a key component of the Waldorf Classroom?

LAURIE: I think that when the practice of chalkboard drawings began in Waldorf curriculum, the culture was not as rich in pictures as it is now. At first, the board drawing gave another dimension to the imaginative content that the teacher presented. But today, visual stimulation bombards the children, so we really need to look at the reason for our chalkboard drawings.

Are they necessary at all? Or do we just do them because everyone else does?

It might be that through the chalkboard drawing we are able to picture something in the subject matter in such a way that it builds upon our imagination.

In other words, a good drawing makes the content of the lesson more, not less— bigger, not smaller.

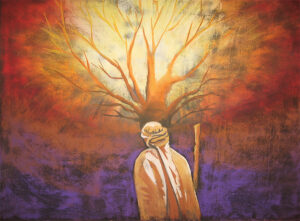

SASKIA: Children need chalkboard drawings now more than ever. There is such busy-ness out in the world that children see more and more. Seeing a picture created by your teacher fashioned for your class is like going to the well. Even while listening to a story, it’s a place can you go and just be for a while.

And chalkboard drawings in Waldorf schools work deeply on the child. They are all about setting a mood in the classroom.

It’s a place for the child to rest their eyes, to dream into, to nourish them. When chalkboard drawings work well, they draw the child in through color, inviting them into a mood to match that time period the class is studying, or the season of the year, or the topic of the block.

I always do my drawings a day or more before I need them. Something happens to a drawing when you step back from it. You need some distance to be able to see it properly, and to tell what else it might need. And I believe the angels always seem to make the last changes.

And what does the process do for the teacher, and for the dynamic of the class?

JAMIE: Above all, chalkboard drawings are a concrete example of a teacher striving. It’s very valuable for a student to see a striving human being in front of them.

So even though I think every teacher finds it challenging, there’s no question that it’s appreciated, regardless of the quality of the drawing. The children find wonder and surprise in anything you put up. There’s a palpable feeling in the class when they see something fresh.

The idea of chalkboard drawing in the Waldorf classroom is to spark an interest: it’s like preparing a gift for the students.

SASKIA: It’s absolutely essential that the teacher works artistically, even if it is challenging. It’s a key component in the whole Waldorf approach of asking teachers to connect with the children in an imaginative and artistic way. Our job is to ensoul the classroom, and the chalkboard drawing is a key part of that.

When a class sighs a contented “Ahhh” on seeing a new drawing, it helps create the calm space both they and the teacher need for learning. A place in which it is good to dwell.

LAURIE: We all struggle with them. I think it’s important that we teachers struggle with our artistic process just as we ask the students to do each day.

The chalkboard drawings are also an art lesson for the class. I hope that my drawings demonstrate for the students that color makes any drawing shine, that skies are not always blue, that many colors make green, and that gesture makes a drawing more lively.

Can you say something about the ephemeral nature of Waldorf Chalkboard Drawings?

JAMIE: It’s hard for teachers to erase something that they’ve worked so hard on.

But in some ways it’s a helpful reminder to them and to the students of how things don’t last forever.

SASKIA: The fact that the drawing is impermanent is important. Just like food, you don’t keep it indefinitely. You use it, and then you must grow it again. There’s something freeing too about the need to change it every few weeks. But there is a sadness: my daughter wept in first grade when a particular drawing disappeared.

How does the style evolve through the grades?

JAMIE: In the earlier grades, the tendency is towards ‘dreamier’ pictures. You may not see faces… more is left to the child’s imagination. In the early grades, we avoid perspective entirely, as this would be too ‘awakening.’ By fourth grade, in particular with the arrival of the Man and Animal block, there’s a shift towards more realistic drawings.

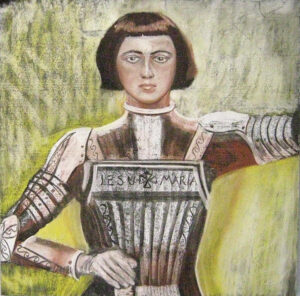

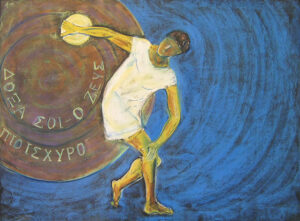

SASKIA: But even in fifth grade, the discus thrower doesn’t have a face with features.

It’s left deliberately abstract enough that each child can imagine themselves as that figure.

How are images chosen?

SASKIA: In the early grades, the drawings always relate to a story. In Waldorf education, we are usually telling stories rather than reading books to the children, so they’re not seeing illustrations.

The drawing assumes great importance.

Perhaps the hardest challenge is to keep the drawings from being too specific. The worst fault is if they become too intellectual, too defined. Less is always more: simplicity is good.

For instance, in eighth grade a ship going towards the horizon speaks more than a whole fleet anchored in a harbor… not only does it feel like something the child can replicate in their own main lesson book, but it allows the child to imagine the ship’s journey as a starting point for their own story.

JAMIE: Teachers will often choose something that is from a story they will tell later on in the block, so that there’s always something for the students to look forward to. Typically, a chalkboard drawing is inspired by something a teacher has seen (in real life, or in researching for the block), but we also try to conjure up from our own imaginations.

LAURIE: I struggled with what to draw for the sixth grade physics block. I ended up doing a drawing of lightning lighting up the sky and infusing the landscape with color. I liked it for a couple reasons. Although I never mentioned lightning in the physics block, I wanted the children to see that physics is in the world around us—not confined to the classroom.

I hoped that the drawing would demonstrate this notion in an unconscious way.

SASKIA: It took me a while to land on the image of the discus thrower for our fifth grade Greek History block; I had come across a statue of a discus thrower and considered a white-on-black representation of it. But I stopped, wondering what that would do for the students. Trying to replicate white-on-black is more of an eighth grade level project.

Another possibility was to portray two runners… but that would cause the child to wonder who was winning, and raise the question of competition, exactly what the block was trying to avoid.

I needed to step back and ask myself what is the gesture of this block? Why are we teaching it? I had to recognize that the Pentathlon is not easy for everybody, and so it was important to note, as a class, that the Greeks didn’t record the names of winners. Their emphasis was on each person’s efforts to strengthen their own body as a way of giving thanks to the gods, each participant giving their best.

So instead, it became a color drawing, displaying the athletic prowess of the thrower, clothed in a tunic which, while not historically accurate, better meets a fifth-grader’s level of readiness for Greek nudity! And for the backdrop, the discus is inscribed with a dedication: “Glory to Thee, O Zeus!”

Sometimes a Waldorf teacher is able to make a “progressive” chalkboard drawing. Can you talk about how and why this is done?

JAMIE: I once did a Noah’s Ark chalkboard drawing for third grade, which developed significantly over time: the first week was the Ark being built; then came the animals; then came the storm. Finally, after the flood, the sun came out, the light changed, hills appeared, and the animals went back out in nature.

There’s a pedagogical value in having something that changes a little over time.

It works with anticipation, which is so important—it’s good for children to have to wait for something.

SASKIA: At Christmas, in the early grades, I once did a Nativity scene, and extra animals would appear at regular intervals. This approach lets children imagine what’s coming… they already start to weave the next step in the picture.

Finally, what do the students say about the chalkboard drawings? What feedback do you get?

SASKIA: Typically, the students never say anything! But I know for certain that the picture works away on them. They definitely notice it right away, they pause and look hard at it, but they don’t always speak.

My feeling is that it’s working away on them at an inner level. Because they experience it as a gift, it’s almost as if they don’t want to unwrap it until they discover what it really is… how it fits into what they’re about to study.

There’s a soul process at work that I try not to disturb, until they are ready to take it in.